As in its more famous neighbouring region, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay reign supreme and, with rare exceptions, are the mandated grapes for the wines.

Major appellations in the Côte Chalonnaise, moving from north to south, include Rully and Mercurey, which produce both red and white wine, Givry, which produces mostly (80%) red wine, and Montagny, which produces white wine exclusively.

Just over half of the 256ha in Givry devoted to red wine is classified as premier cru, divided among 38 vineyards. By comparison, 76% of Beaune’s 364ha devoted to red wine is classified as premier cru.

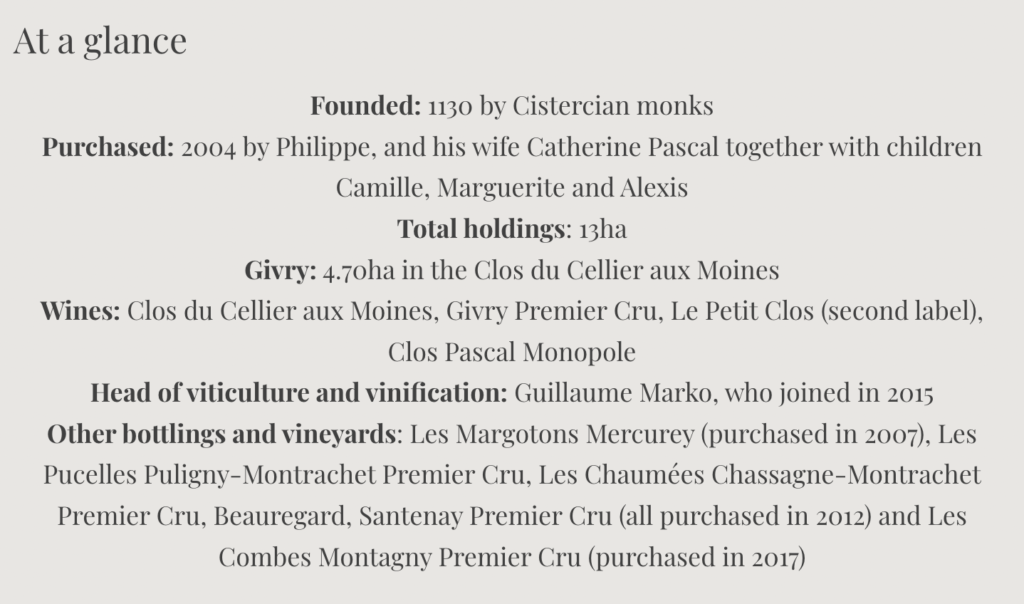

The 12.9ha Clos du Cellier aux Moines is considered to be one of the best. Domaine du Cellier Aux Moines, one of the top producers in Givry, owns the largest piece. Their choice 4.70ha are planted to Pinot Noir in the mid and upper slope of the vineyard, affording ideal exposure.

Domaine Baron Thénard owns just over 4.4ha in the mid and lower part of the vineyard and Domaine Joblot has about 2.2ha in the lower part.

History

The Domaine du Cellier Aux Moines traces its origins to the 12th century when it was under the auspices of the Cistercian monks, (moines is French for monks) who also founded the famed Clos Vougeot at about the same time.

Fast forward to 2004, when Philippe and Catherine Pascal took over the Domaine and built something unique in Burgundy—a fully gravity-flow winery.

Initially, they used the 12th-century building for the winery, which Philippe Pascal noted was ‘great for pictures, but a nightmare for the winemaker.’ The Pascals restored it so beautifully that now the French government lists it as one of the country’s historic sites.

An abandoned quarry adjacent to the domaine allowed them to create a winery with three of its four levels underground. It took two years to design and another two to build but was ready for the 2015 harvest.

The advantage of a purely gravity-flow winery, aside from its energy efficiency, is the ability to move the grapes, juice, and wine from harvest, to fermentation, to barrel ageing without the use of pumps. Pumping potentially exposes the wine to oxidation and other stress.

In addition to controlling temperature naturally, the winery’s underground positioning controls humidity, which reduces evaporation – the angels’ share – during barrel ageing. Another plus: the configuration allows them to bottle the wine unfiltered because of the natural sedimentation that occurs prior to bottling.

Making the dream a reality

Ever since their early days together, Philippe, an agronomist by education, and Catherine, a lawyer from Beaune, always dreamed of owning a small vineyard together ‘somewhere, someday,’ remarked Philippe. He continued, ‘We wanted to do it with our own hands … and get our feet wet.’

In his previous life, Philippe was with LVMH-Moët Hennessy as CEO of Veuve Clicquot Champagne and CEO of Moët Hennessy. Somewhat philosophically, he remarks how ‘life sometimes gives us a wonderful opportunity to do different things.’ So, at age 58 – he discreetly omits his wife’s age – they purchased the domaine and embarked on a new career.

Looking back on the last 16 years, he said that it turned out to be more complicated than anticipated. ‘Even in France, where everything is complicated, this was more complicated than we imagined.’

Again, with that Gallic philosophy, he observed that there was a beauty in the opportunity to learn something new. They took viticulture courses, learned from other vignerons and embraced the ‘less is more’ philosophy. With unbridled enthusiasm, he exclaims: ‘it was a fascinating learning experience.’

Building a team

To guide the conversion to organic farming, they recruited Guillaume Marko, who had worked at the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, as well as Domaine Arnoux Lachaux in Vosne-Romanée and Domaine Frédéric Magnien in Morey Saint Denis.

Eventually, with the 2017 vintage, they had converted the entire domaine to biodynamics. The Pascals are firmly committed to biodynamics because, as Philippe notes: ‘it forces us to be a better viticulturist.’

They fine-tuned the viticulture, replanting with a massal (field) selection of Pinot Noir vines that produced smaller bunches of grapes with smaller berries. With replanting, they embraced the parcelaire approach to the domaine, sub-dividing their 4.8ha into half a dozen plots depending on the characteristics of the soil.

Philippe credits the help they received from Sylvain Pitiot who used a similar technique with great success when he was in charge at Clos de Tart. He thinks that embracing biodynamics ‘sharpens the expression of each plot.’

Work in the vineyard

With a laugh, Philippe describes the parcelaire approach as a ‘headache, but a great tool.’ During the growing season, they follow each of the plots carefully to allow them to individualise the timing of the harvest, which, even with such a small domaine, can vary by up to a week.

Their primary concern is to wait for physiologic ripeness – the ripeness of the tannins – rather than ripeness as measured by sugar level. He explains that since they perform whole bunch fermentation—vendange entier—which means the stems are included with the berries, the stems must be ripe and brown with fully mature tannins.

The Pascals have revived and replanted Pinot Noir in a tiny, 0.26ha, walled plot, Clos Pascal, that had been abandoned after the phylloxera crisis.

Marko trained the vines on poles (échalas), using an old, traditional, training system to limit yield and reduce stress on the vines. Though it had originally been classified as Premier Cru, French politics being what they are, it was declassified to, and bottled as, a village wine under pressure from other Givry growers, according to Philippe.

Whole-bunch

Two major advantages of whole-bunch fermentation, according to Philippe, are having intact berries and using the stems as ‘a sponge.’ Since there is little destemming, the majority of the berries are virtually intact prior to fermentation. When fermentation begins it does so within the berry and then they burst. Pascal believes that even this brief intra-berry fermentation captures aromas better and results in better extraction of flavours. He adds that stems absorb unpleasant tannins, like a sponge. In short, he’s convinced that, if done properly, the wine will be more refined with a more elegant structure and better aromas.

They train their harvesters to pick only mature berries, leaving everything else for the birds. The serious sorting begins at the sorting table at the cuverie under the guidance of Catherine. There, workers cull unripe or otherwise less-than-ideal berries to be used for a second wine, another idea they learned from Pitiot.

Lots from barrels that don’t measure up to their standards also find their way into the second wine, Le Petit Clos du Cellier, which they bottle under the Givry, not Givry Premier Cru, appellation, and sell only within France.

A third of their production typically winds up in Le Petit Clos, according to Pascal. He believes they’ve achieved a tremendous leap in quality by using the parcelaire approach in the vineyard and the introduction of a second wine in the winery.

Their incremental improvements in the vineyard, care with the yields, and their unique winery together explains the dramatic increase in quality of the wines since the Pascals took over. It’s fascinating to see the impact of these changes on the wines.

The tasting

My assessment is based on a vertical tasting of 12 vintages of Domaine du Cellier Aux Moines’ Clos du Cellier aux Moines from 2006 to 2019. Since Covid-19 prevented me from going to the estate, they sent me the wines, including an unfiltered, unsulfured barrel sample of the 2019.

All the wines, even the barrel sample, arrived in excellent condition, no doubt because the Pascal’s daughter, Margot, carried them back personally to New York, where I collected them.

Overall, it was an impressive line-up of wines. Full tasting notes are below, but first, an overview and some highlights.

The 2006, made early in the Pascal’s ownership before they initiated many changes, showed the potential of the site. Fully mature, it conveyed the magic of mature Burgundy with its combination of dried fruit and savoury elements.

The quality of 2009 and 2010 vintages, a time before the changes had achieved their full impact, reinforced the concept that their terroir was exceptional and reflected these two great vintages, especially for red Burgundy.

The 2012, from a difficult vintage, showed the value of their replanting and parcelaire approach. Philippe described it as their ‘first replanting harvest’ because a third of the final blend came from those vines. Nearly mature, the 2012 was a real success, conveying a wonderful balance of concentration, complexity, and freshness.

With its enormous leap in quality, the 2015 heralded the beginning of a new era at the domaine. The 2015 and all subsequent vintages were now on a higher plateau. The wines displayed a finer texture – cashmere compared to lambs wool – compared to the previous vintages.

Three changes, occurring simultaneously, explain the leap. Firstly, 2015 was the first vintage to be vinified by Guillaume Marko, confirming the value of a talented winemaker. It was also the first vintage vinified in the new winery, which seems to validate the importance of gravity flow. And it was when the domaine started to bottle a second wine, which elevates the quality of the grand vin by eliminating lesser quality lots.

The 2017, the first year the domaine was almost fully biodynamic, makes a powerful argument for that technique. With silky tannins, it was a masterpiece of grace and power. Philippe emphasises that since 2017 was a naturally generous vintage coming after low-yielding 2016, controlling yields was key to quality. Variable yields explain the Janus-like nature of the 2017 vintage for reds in general – some are forward and charming, while others are structured and concentrated. He felt their yields at about 40hl/ha, well below the maximum allowed of 52hl/ha for Givry Premier Cru, resulted in the ‘right balance between concentration, backbone and fruit.’

Lastly, from this tasting, I estimate the peak window for drinking Domaine du Cellier aux Moines to be about 12-15 years for wines from the best vintages and six to eight years for wines from lighter years.

Eight hundred years after its founding, the Domaine du Cellier aux Moines has become a rediscovered star in the constellation of Burgundy wines.