St-Julien is the quintessential expression of red Bordeaux, displaying grace and power without being overbearing.

It’s also the smallest of the major communes of Bordeaux and the one with the largest percentage of classified growths, as measured by acreage.

Indeed, 90% of the vineyards belong to the classified growths. St-Julien also claims to have the lowest average yield of all the major Médoc appellations, according to noted Bordeaux-authority Jane Anson.

Although Château Talbot is not the most prestigious property in St-Julien – that likely goes to Château Léoville Las Cases – Château Talbot is as characteristic of St-Julien as St-Julien is to Bordeaux.

And, as the tasting notes show, Talbot is an estate that is upping its game.

Old Talbot

The estate is supposedly named after Sir John Talbot, the 1st Earl of Shrewsbury – Shakespeare’s ‘Old Talbot’, also known as ‘the English Achilles’ and ‘Terror of the French’.

A veteran of the later campaigns of the Hundred Years War and the last English lieutenant of the Duchy of Aquitaine, he was killed at the Battle of Castillon in 1453.

This disaster of English arms effectively ended the century-long conflict, and resulted in the French taking control of Bordeaux after 300 years of English rule.

The estate has passed through only a handful of owners down the centuries. A map of 1785 marks an area of St-Julien as ‘Talbot’ and there is a house (which likely became the château), owned by the Delage family.

Not long afterwards it was bought by Jean-Jacques d’Aux de Lescout and passed down to his son, Henri-Raymond, who did much to expand the property. In 1899 Arnaud d’Aux sold the estate to Albert Claverie, and Désiré Cordier purchased it in 1918.

The Cordier family still owns Château Talbot, with Nancy Cordier-Bignon and her husband Jean-Paul Bignon being the current directors. Eric Boissenot consults.

Château Talbot, classified as a 4th growth in the Médoc Classification of 1855, is one of St-Julien’s largest estates, encompassing about 110ha, in one single block around the estate.

Vines & winemaking

At about 25 metres above sea level, it is ‘high elevation’ for the Médoc. Talbot’s plantings reflect what’s grown in St-Julien in general: roughly 68% Cabernet Sauvignon, 28% Merlot, and 4% Petit Verdot.

There used to be Cabernet Franc in the blend but it was pulled out in 2007 by then-general manager Jean-Pierre Marty. His successor, Jean-Michel Laporte agrees with this move, believing that, unlike on the Right Bank, Petit Verdot is a better ‘complementary variety’ for Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot than Cabernet Franc.

The grapes for Talbot come from vines that average 40 years old. They are harvested entirely by hand.

The harvesters do an initial sorting in the vineyard, eliminating diseased parts of bunches. In the cellar, the grapes are destemmed.

Then, state-of-the-art optical and densimetric sorting removes single berries that are not up to snuff.

After fermentation, the grand vin ages in oak barrels for about 16 months in an architectural gem of a barrel cellar.

Ahead of the curve

Talbot started producing a second wine, Connétable, beginning with the 1979 vintage, before many other Médoc producers adopted that practice.

Connétable typically comes from younger vines, but still averaging 30 years old, or those situated in less desirable parcels with sandy soils.

In contrast to the grand vin, Connétable is vinified in stainless steel tanks. It usually comprises about 40% of Talbot’s annual 400,000 bottle production.

Five of Talbot’s 110ha are devoted to white grapes, Sauvignon Blanc (80%) and Sémillon, from which it makes Caillou Blanc.

The blend of the wine typically follows the proportion of each in the vineyard. Although the vines lie within the St-Julien appellation, Caillou Blanc carries the Bordeaux Blanc appellation because regulations for St-Julien only permits red grapes.

Flying under the radar

Château Talbot frequently flies under the radar and fails to receive the accolades it deserves, perhaps because it is such a large estate with such a large production.

Whatever the reasons, it is a boon for consumers because the wines are widely available and the prices, at least compared to other cru classé, are reasonable.

As you’ll see from the tasting notes below, the wines of Château Talbot have become more refined and polished over the last two decades.

Jean-Michel Laporte, who ran La Conseillante for nearly a decade and has been the general manager and winemaker at Talbot since 2018, attributes the enhanced refinement to changes that his predecessor, Jean-Pierre Marty, made – starting with the 2006 vintage.

Laporte notes that Talbot was, ‘late to embracing new technology’ and explained that Marty and his team took a more ‘modern and cleaner approach to winemaking’ at Talbot.

Laporte emphasises that when he took over at Talbot he ‘didn’t want to change the style’. He just wanted to add slightly ‘more depth to the mid-palate’.

Laporte adds modestly that he ‘adjusted some details’ in the vineyard and the cellar. His aim in general, whether at Conseillante and now at Talbot, is ‘to preserve balance, have ripe tannins, and avoid astringency’.

In the vineyard, Laporte removed leaves from the vines earlier in the growing season to achieve better maturity of the grapes and reduce the chance of disease.

He notes now that while overall average yields were fine, he found that decreasing yields in a few of the plots improved quality.

Savoury & savoured

In the cellar, he started the pumping over earlier during fermentation, when the alcohol level is low, to extract softer tannins from the skins instead of more astringent ones from the seeds.

He also slightly increased the amount of new oak barrels for ageing, from 50% to 60% to bring softer, more refined tannins to the wine.

In addition to greater refinement of the wines over the last two decades, the tasting notes indicate that the wines from Château Talbot develop beautifully with bottle age.

They deliver an engaging and alluring combination of fruitiness mixed with that illusive ‘not just fruit’, woodsy, savoury character.

Another lesson: even mature wines evolve in the glass, so they should be savoured, not rushed.

Château Talbot: 14 notes from 2020-1966

Wines are listed in order of descending vintages.

Château Talbot, Caillou Blanc, Bordeaux Blanc, Bordeaux, France, 2020

Château Talbot, Caillou Blanc, Bordeaux Blanc, Bordeaux, France, 2020

Although Sauvignon Blanc’s distinctive varietal character is readily apparent on the nose, a subtle creaminess appears on the palate, creating a harmonious counterpoint and a balanced wine. Fresh and vigorous, a delectable touch of bitterness in the finish vividly makes the point that this is not just a fruity varietal wine.

Michael Apstein – Points: 91

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2030

This is an confident and attractive Caillou Blanc, showing soft apricot and white pear flesh through the mid palate. Not hugely varietal, it is more about the texture of the wine, with bitter almonds on the finish that give both pep and focus.

Jane Anson – Points: 92

Drinking Window: 2021 – 2025

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2020

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2020

The long and polished 2020 Talbot leads with great fragrance followed by black fruit notes and even a hint of tar. Overall, it is less muscular, but still concentrated, and more refined than the densely paced 2018, conveying a classic St-Julien temperament. Its suaveness makes it surprisingly approachable even now. The energy and refinement of the 2020, like the 2019, make one wonder whether Laporte consciously turned down the volume after the massive 2018.

Michael Apstein – Points: 96

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2045

This is a great Talbot, a real success for the château. Subtle and deft touches throughout, from the smoked turmeric notes that lace the black fruits to the finessed aromatics that accompany the body of the wine. Balance and freshness, and a saline edge to the finish that is extremely moreish. Three years with Jean-Michel Laporte as director and he is doing great work.

Jane Anson – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2026 – 2040

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2019

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2019

The youthful and energetic 2019 Talbot, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Petit Verdot, retains grace despite its ripeness. Still bold for a St-Julien, it shows the restraint and elegance of Talbot. Brimming with black fruit, and a suave, silky texture, the savoury side has just started to peek out. With its impeccable balance, I’m sure it will develop gorgeously.

Michael Apstein – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2045

St Julien’s largest property at 110ha (up there with Lagrange if you’re keeping track), this has lovely plump black fruits on the nose. Takes hold right from the start, with clear tannic build and a silky character to the tannins. This continues the run of good vintages that Talbot has been producing since 2016. Well balanced, with plenty of St Julien character. Tasted twice two weeks apart. Highest ever level of Cabernet Sauvignon at the estate. Harvest 19 September to 8 October. 60% new oak.

Jane Anson – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2026 – 2040

Such an expressive nose, majoring on floral black cherry and dark chocolate notes. High toned on the palate you can feel the freshness which is so welcome. This has nice appeal, quite a gentle style, definite grippy tannins but they are round with smooth edges. Nice impact, not showy or too over the top. Just a bit of rusticity on the finish still with licks of liquorice spice.

Georgina Hindle – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2023 – 2035

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2018

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2018

The youthful and sumptuous 2018 comes in a strikingly heavy engraved bottle that celebrates the 100th anniversary of Cordier ownership. It is both delicious and atypical. Atypical, because this ripe and juicy wine, weighing in at a stated 14.5% alcohol, is unusually muscular for St-Julien. Delicious, because its exuberant fruitiness and silky, suave texture makes it hard to resist now. More in keeping with a California-style wine than a St-Julien it is, nonetheless, a marvellous combination and balance of power and elegance. Laporte describes the 2018 as ‘a garage wine’ and not the style he wants to make. He attributes its size to the warmth of the vintage and thinks it will settle down with proper aging.

Michael Apstein – Points: 94

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2045

A great St-Julien that reflects the estate more than the vintage – a definite compliment to the winemaking team as well as those 50-year-old (on average) vines that are less swayed by climatic changes. This is full of blackberry and bilberry, with a touch of tobacco on the nose. There’s good sweetness to the fruit, and although it’s not quite as punchy, deep or concentrated as some, this means that it has a beautifully balanced appellation signature. 45hl/ha yield. 60% new oak.

Jane Anson – Points: 94

Drinking Window: 2027 – 2040

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2015

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2015

The gentle 2015 Talbot shows the charms of claret. Not a powerhouse, it caresses the palette. Its restraint and elegance are the epitome of Talbot. With its mixture of fresh dark fruit accented by a delicate cedar or tobacco-like spice, it’s almost ready. The suave texture of this restrained charmer means that for some, it is ready.

Michael Apstein – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2040

Another excellent vintage, where we see Talbot growing in precision. This is soft and well-placed, building in power over the enjoyable palate. The softness of the fruit means I might expect the 2014 to age longer, but no one is going to complain about the enjoyment here, and it still retains its St-Julien balance. Aged in 50% new oak.

Jane Anson – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2040

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2014

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2014

Here the lovely cedar nose draws you in and leads to an elegant combination of dark fruit and mature, leather-like nuances. The tannins are not as fine as more recent vintages but allow support without being intrusive. Alluring maturity comes out at this decade-old beauty.

Michael Apstein – Points: 92

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2030

Good, firm fruits are well placed, with notes of cedar, liquorice and cassis – this really is an enjoyable Talbot that offers the promise of a long life. There’s enjoyable grip and tenacity through the palate, with spicy, flexible tannins. It has a substantial weight that fleshes out and deepens. It’s savoury in the French sense of ‘savoureux’, with connotations of juiciness and a ‘give me more’ appeal. Aged in 50% new oak.

Jane Anson – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2024 – 2038

Deep colour and rich fruit – good blackberry spice and quite smooth flavours. Will open up early but can last.

Stephen Spurrier – Points: 89

Drinking Window: 2018 – 2028

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2009

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2009

A hint of brick colour at the edge belies the youthfulness of the gorgeous 2009 Talbot. Succulent black fruit sits on a firm but suave base. Savoury mature nuances peak out, but this beauty has miles to go before it sleeps (apologies to Robert Frost). This poised delight shows the charm of St-Julien.

Michael Apstein – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2040

As with the 2005 vintage, you immediately feel the effects of the year translate into more layers of flavour. I love this 2009, because it is still a classic Bordeaux, well balanced in alcohol – nothing excessive but it allows the château to show the best of itself. Sometimes Talbot can be a little reserved, a little too classical, but here the fruit is generous, dark, brambly and still young. The mint notes remain fresh, but the graphite and slate are more evident, and you can feel the tug of a great Cabernet here. Aged in 50% new oak.

Jane Anson (Dec 2017) – Points: 94

Drinking Window: 2020 – 2038

A well structured wine with smoke and cedar edging to the aromatics, a generous, ripe fruit structure and soft, well-integrated tannins. It has clear appeal. At this stage, the 2005 seems to better encapsulate the heart of St-Julien but the 2009 offers an extremely enjoyable wine, even if less typical of the appellation.

Jane Anson (Feb 2019) – Points: 94

Drinking Window: 2019 – 2036

Elegant new oak marks the nose, as well as stylish cassis fruit. Evidence of tightly knit, ripe fruit on the palate. Quite dense – the tannins are present but ripe and the acidity correct. Poised and long, with fine potential; will come out of its shell.

Stephen Brook, Alun Griffiths MW, Steven Spurrier – Points: 90

Drinking Window: 2015 – 2030

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2006

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 2006

After almost two decades, the dazzling 2006 Talbot is entering its window of maturity. Gorgeous aromatics suck you in and the palate does not disappoint. Alluring cedary nuances add complexity and a ‘not just fruit’ quality to its weighty black fruitiness. Many will find this fresh and poised Talbot perfect for current consumption while others will still find it youthful and wish to cellar it for a few more years to allow for even more evolution. 62% Cabernet Sauvignon, 31% Merlot, 5% Petit Verdot, 2% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 94

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2035

These wines demonstrate how Bordeaux somehow straddles the midpoint between Burgundy and the New World, and you see here why they work so well for so many palates: they have tannins and power, but are also elegant and refrain from giving too much away too soon. 2006 is another classic Médoc year where the tannins are firm and the wine is elegant and rich, but not showy. The 2006 has taken its time to come around and it remains fairly restrained, but this is still a beautifully classic St-Julien. Don’t leave Talbot for as long as, for example, Château Léoville Las Cases, but it will still reward with true St-Julien balance and freshness. This is very good.

Jane Anson – Points: 92

Drinking Window: 2018 – 2030

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1995

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1995

The suave and clearly mature 1995 Talbot, from half-bottle, was still fresh 29 years later. A touch of cedar accented fading fruitiness in this mid-weight beauty. It’s a graceful wine that manages to keep expanding as it sits in the glass. 58% Cabernet Sauvignon, 33% Merlot, 6% Petit Verdot, 3% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 92

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2030

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1990

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1990

Unsurprisingly given the stature of the vintage, the 1990 Talbot was stunning. A garnet slightly brown tinged rim indicates its age. Rich, certainly, yet refined, it conveys the understated power and elegance of St-Julien in general and Talbot in particular. Here’s a classic mid-weight wine delivering both fading plum-like fruit and woodsy nuances along with a hint of balsamic-like notes. 68% Cabernet Sauvignon, 24% Merlot, 5% Petit Verdot, 3% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2030

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1988

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1988

The 1988, from a 6-litre bottle, has turned out splendidly. The hard tannins characteristic of the vintage – and apparent when this wine was young – have melted away to reveal a supple texture and a panoply of dark fruit and coffee-like savoury elements. Still fresh, it likely has more evolution in it. 70% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, 2% Petit Verdot, 3% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2035

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1986

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1986

In a word, gorgeous. The ferocious tannins of the vintage have melted away but still linger in the background, providing structure to its plum-like fruitiness. Hints of cedar peek out. Despite being another bold expression of Talbot, it maintains a graceful profile. Fresh and youthful still, you’d never guess it’s 38 years old. 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 28% Merlot, 5% Petit Verdot, 3% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 95

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2044

The weather in 1986 suited Cabernet extremely well, with some early September rains after a good July and August, then fine weather right through the rest of the month and into October, giving exceptional harvesting conditions. You can see it in the colour, and smell it on the nose that remains subdued but confident. It’s a lovely wine, a little austere compared to some of the older wines but full of firm, dark blackberry and blackcurrant fruit, tight tannins, and with dancing acidity across the palate that suggests it’s going nowhere anytime soon. The fruits are not primary but are at least in the early bloom of Cabernet Sauvignon, and it has a mouthwatering finish. A fine and well-structured St-Julien, with plenty of appellation typicity. 3% Cabernet Franc makes up the blend.

Jane Anson – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2018 – 2040

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France 1983

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France 1983

Like the 1990, the mature 1983 Talbot leads with a browning edge and similar subtle balsamic notes. Dark fruits mingle effortlessly with the cedar, coffee, and leathery nuances of maturity. Still fresh at 40+ years, the 1983 is a marvellous success, especially for the vintage. 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 27% Merlot, 4% Petit Verdot, 4% Cabernet Franc.

Michael Apstein – Points: 96

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2030

It is difficult for me to remember a wine that gave such incredible instant gratification on pulling the cork. Smokey, leather, pencil shavings jump out the glass from minute one. The palate is fully evolved and the tannins are perfectly integrated. This is a wine that gives instant pleasure with no need to decant. So moreish with wonderful balance. Nothing out of place. I would suggest not opening too far in advance and don’t let it hang around. If you have this in your cellar, pull a cork today… you will not regret it.

Gareth Birchley – Points: 93

Drinking Window: 2023 – 2023

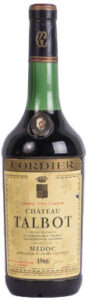

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1966

Château Talbot, St-Julien, 4ème Cru Classé, Bordeaux, France, 1966

Browning edges proclaim its age. Clearly mature with alluring leathery and cedar nuances, the graceful 1966, even at 58 years old, is still fresh, not tired, and a delight to drink. The dark fruitiness has faded, but the wine’s stature and graceful profile has not. Long and refined, it’s a classic, old-style St-Julien that reinforces the motive for ageing wines. 63% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 4% Petit Verdot, 3% Cabernet Franc

Michael Apstein – Points: 96

Drinking Window: 2025 – 2066