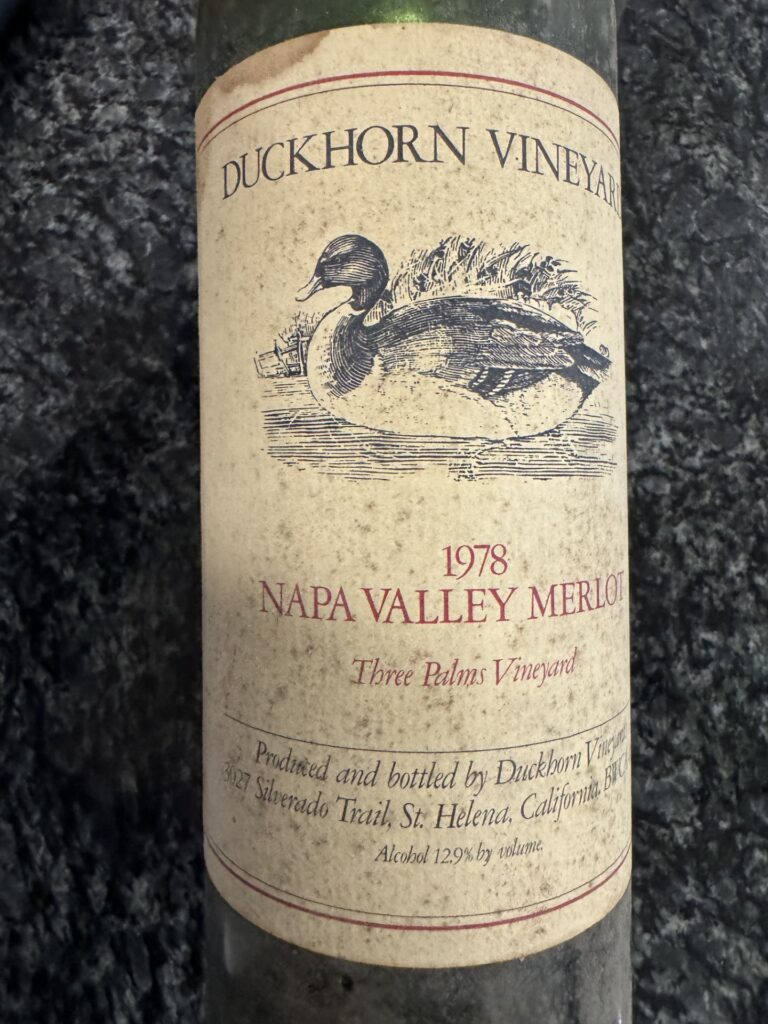

Duckhorn Vineyards 1978 Merlot Three Palms Vineyard Napa Valley California 97

Duckhorn Vineyards, founded in 1976 by Dan and Margaret Duckhorn, released its first wines two years later, from the 1978 vintage: 6,000 bottles each of a Cabernet Sauvignon and this Merlot.… Read more