It’s amazing what money and dedication to a goal can do. Suntory, the Japanese multinational brewing and distilling company, purchased the neglected and run-down Château Lagrange (an estate classified as a Third Growth in the famed Médoc Classification of 1855) in 1983 for a reported 10 million U.S. dollars—a bargain by today’s standards. (In 2019, each of four Cru Classé Médoc estates reportedly sold for more than 100 million U. S. dollars.) The property was in abysmal shape when Suntory purchased it. Roughly half of its 118 ha (300 acres) of vines were not even in production. And among the ones that were, a significant proportion were diseased. Suntory wound up pouring three times as much money over the next few years into renovating the cellars and vineyards, and most importantly, hiring a team that shared their vision of making the best wine possible. Matthieu Bordes, now the estate’s general manager and chief winemaker, recounts how initially the Bordelais were concerned, and even a little frightened, that a Japanese company was going to buy a prime Bordeaux château. But their apprehension evaporated when it became apparent that Suntory was in it for the long haul. Bordes explains that they (Suntory) are great to work with, have lots of money, and understand the long-term nature of the project, which was key given the work that was needed.

To celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Suntory’s ownership of Château Lagrange, Bordes recently hosted a vertical tasting of their wines, from 1982 to 2019, in New York City. The most important take-away from the tasting was how much the wines, both le grand vin and the second wine, had improved under Suntory’s stewardship. Pricing has not yet caught up to quality, making Château Lagrange a relative bargain among Classified Bordeaux. Meanwhile, the so-called “second wine” of the estate, Les Fiefs, allows consumers to get a peek at the stature of a top Bordeaux at a fraction of the price. It is a consistently good buy, and, as the tasting notes show, also develops beautifully with bottle age.

Marcel Ducasse, whom Suntory put in charge of the project in 1983, once told me that the quickest way to improve a wine was to create a second wine, which is exactly what he did, creating Les Fiefs de Lagrange in 1983. Previously, “tous dans la meme fosse,” quipped Marcel (everything in the same hole). Bordes explains that “everyone has young vines (that typically produce inferior fruit) and press wine,” or diseased vines and grapes so it makes no sense to blend it all together. By making a strict selection, bottling only the best of the harvest, a much better wine appears virtually overnight as opposed to waiting a decade or two to rejuvenate vineyards. On average, Lagrange now typically bottles a staggering 60 percent of their total production as the second wine, Les Fiefs de Lagrange.

Of course, a rigorous selection of the best grapes means less wine going into le grand vin. The financial theory goes that you can sell the smaller quantities of the newly improved grand vin (1st wine) at a higher price and supplement the revenue with sales of the 2nd wine. That’s the theory. That calculus may work for the First Growths, but not necessarily for the less prestigious estates. In practice, Bordes recalls that Lagrange did not show a profit for the first 14 years Suntory owned it, which seemed to be of little concern to them since the estate was only one of their 300-plus companies and even today has no real impact on the company’s bottom line.

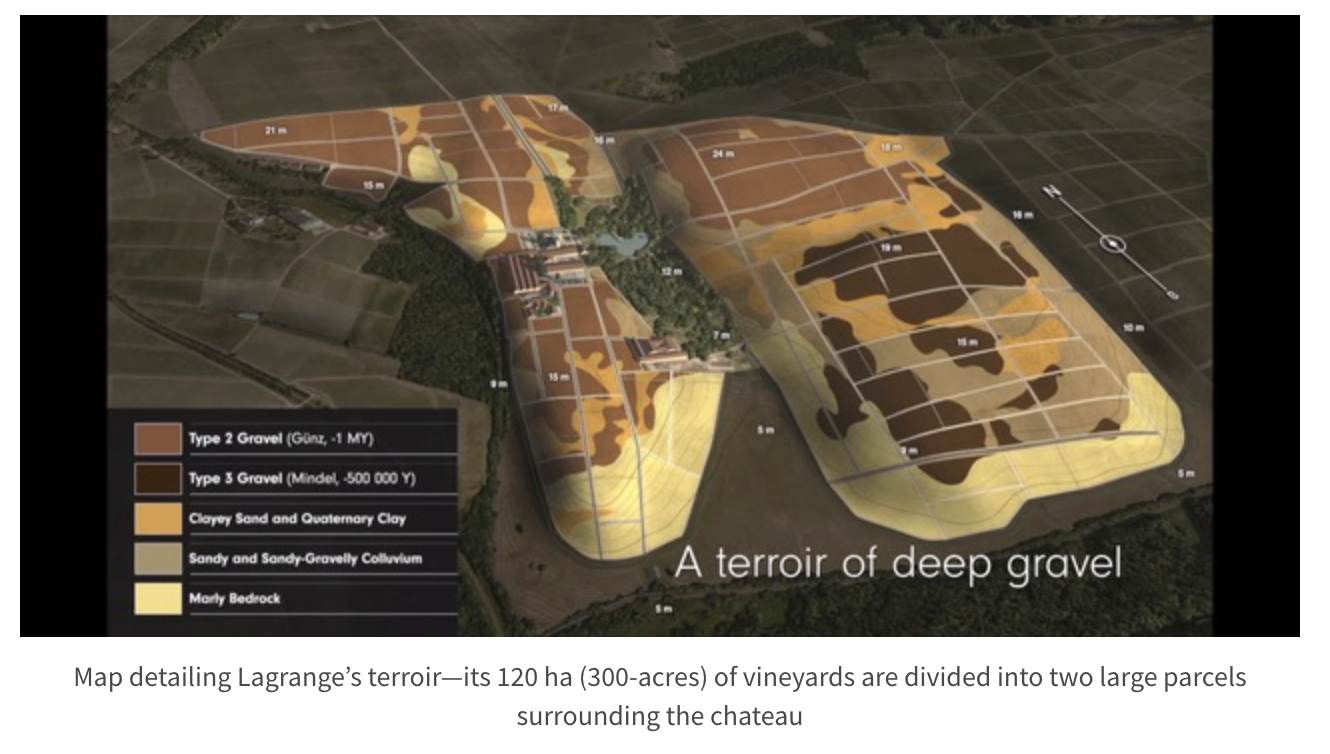

Bordes, who joined Ducasse’s team in 2006 and became General Manager and head winemaker in 2013, explained that more precision in the vineyard and the cellar took the quality of both le grand vin and Les Fiefs to a new level. By precision, he means knowing the best places to plant each of the three varieties of reds, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Petit Verdot, that comprise both le grand vin and Les Fiefs. Precision also means tending and harvesting each plot individually. So, one of the first things Bordes did, in 2008, soon after he arrived, was map the soils of the vineyard. Even as dilapidated as it was, Lagrange had the distinct advantage of its terroir—its 300-acres of vineyards were divided into two large parcels surrounding the chateau. Unlike many Bordeaux estates which have added plots, sometimes of dubious quality, over the years to their estate, no additional land in inferior parts of St. Julien had ever been incorporated into Château Lagrange. Bordes’ team next drilled 200 holes and analyzed the soil, discovering seventeen different types that allowed them to divide the vineyard in 103 unique plots.

Of course, precision in the vineyard doesn’t do any good if the grapes from each plot cannot be vinified separately. Bordes recounted how Suntory was initially hesitant to invest in 100 new small, but expensive, stainless-steel tanks that would be used for only a month or two a year to replace the 54 larger vats they currently had. So, Bordes convinced them to start with a few. Everyone saw the leap in quality. Now, Bordes works with 102 small vats for their 103 parcels. Money certainly helps.

Bordes can now predict, with about 80 percent accuracy, which plots will deliver grapes for le grand vin and which plots’ grapes will wind up in Les Fiefs de Lagrange. For the other 20 percent of plots, he says, with a typical Gallic smile, “ça depends” (it depends). There are years, he explains, when he is surprised to find that even relatively young vines have produced grapes of sufficient quality to qualify for le grand vin.

The farming has changed to a more Japanese approach of organic and sustainable since Suntory took over. Bordes notes that the Bordeaux maritime climate makes exclusively organic farming difficult, if not impossible. So, about one-third of the vineyards are farmed organically with a noticeable decrease in use of chemicals. Their goal is to be fully sustainable. To deal with climate change, they no longer remove leaves from the south or west facing rows, which helps keep the grapes in the shade. They also stopped the practice of de-acidification of the wine in 2009, since climate change robs the grapes—and subsequently the wine—of needed acidity. As a result, and as the tasting notes show, the wines have an invigorating freshness.

Precision in harvesting is critical, according to Bordes. Delaying picking, even for a day or two, for lack of workers can throw a batch of wine out of balance as sugar, and resulting alcohol, levels, rise. So, instead of relying on a communal labor pool, Lagrange employs its own team of harvesters, mostly from Belgium or Spain, who are always available. They may sit idle for a day or two, but when Bordes thinks a parcel is ready, he has the workforce necessary and ready to go to get the grapes to the winery.

Bordes also attributes the increased quality to the 60 ha (150 acres) of vines that Ducasse planted in the 1980s, which are now old enough to produce fruit capable of being included in le grand vin. Currently, Cabernet Sauvignon represents 67 percent of plantings, followed by Merlot at 28 percent, and Petit Verdot at five percent. When replanting—they replant about 8 ha (20 acres) a year—they favor Cabernet Sauvignon over Merlot because with the warming brought about by climate changes, Cabernet can ripen better, replacing its potentially green tannins with supple ones. This effect is seen in the blend of le grand vin over time with the proportion of Cabernet increasing from 46 percent in 2005 to 86 percent in the 2022. Bordes believes that Cabernet Sauvignon will comprise 90 to 95 percent over the blend by 2043. Although he likes Merlot, Bordes says, it must be planted on “great soil.” Bordes describes Petit Verdot as the “doctor wine” that can provide a boost of tannins, acidity, and alcohol.

Another reason the wines have gotten far better, according to Bordes, is the meticulous care handling and then selecting the grapes from their one million vines. Harvest is done entirely by hand. Harvesters put grape bunches into small baskets to minimize bruising the fruit. Since the vines surround the chateau, the grapes get to the winery within 10 minutes of harvest, minimizing the opportunity for oxidation. At the cuverie, the bunches are spread on a vibrating table so workers can remove those that are diseased as well as extraneous material. The bunches are then destemmed. The destemmed grapes move to another vibrating table for further human inspection and sorting. Then, the 1.5 billion berries go through an optical scanner to detect defects not seen by the human eye. Bordes says though the optical scanner is new—they rented it in 2009 and purchased it the following year—he “could hire someone who worked in a cellar 150 years ago because nothing there has changed.” They still fine with egg whites and bottle the wines themselves.

In addition to the increased quality of the wines due to the changes they’ve made at Château Lagrange over the decades, Bordes believes that the “drinking window,” as he refers to it, has expanded. He prefers to drink le grand vin at between eight and 25 years of age.

Château Lagrange started producing a white wine, Les Arums de Lagrange, in 1996, from a blend of Sauvignon Blanc, Sauvignon Gris, and Semillon planted on about 4-ha (10 acres). It has become quite popular, especially in Japan where they sell 70 percent of the current 40,000 bottle annual production, allowing them to expand the plantings to its current 11 ha (28 acres). Les Arums is bottled in a clear white bottle, instead of the traditional green one, to suit the Japanese preference.

In 2012, Lagrange started bottling a wine, called Haut-Médoc de Lagrange, made from grapes grown just outside the St. Julien appellation from land they purchased in the Haut-Médoc appellation. With the 2019 vintage, they changed the name to Pagus de Lagrange to comply with appellation regulations.

The wines in this tasting report.

Château Lagrange Les Arums de Lagrange 2019 Bordeaux Blanc 93

The remarkably fresh, especially given the weather, 2019 Les Arums delivers the engaging fragrance and attractive bite of Sauvignon Blanc combined with a subtle creaminess that I ascribe to Semillon. Wonderfully uplifting freshness in the finish amplifies its appeal. A blend of Sauvignon Blanc (77%) and Semillon (23%). Drinking window: 2023– 2026.

Château Lagrange 2019 Saint Julien Cru Classé 97

Bordes relates how he always speaks with his Suntory bosses before making the blend to get an idea of how much grand vin to make. For the superb 2019 vintage, his bosses told him that, as always, they wanted him to make the best wine he could, but in 2019 they really wanted the very best wine even if it meant making far less of it. So, a measly 30 percent of the production—the lowest ever—went into le grand vin for the 2019. The succulent and suave 2019, filled with a seamless mixture of black fruits and minerals, reflects the smashing quality of the vintage. Even with the high percentage (80%) of Cabernet Sauvignon, the tannins are smooth and silky at this stage, a character that Bordes attributes to climate change. The 2019 displays a Pauillac-like power and minerality without losing any of the quintessential St. Julien balanced and elegance. This fleshy wine should develop beautifully over decades. The blend is Cabernet Sauvignon 80%, Merlot 18%, Petit Verdot 2%. Drinking window: 2029-2059.

Les Fiefs de Lagrange 2016 Saint Julien Cru Bordeaux 93

The depth of ripe, succulent black fruit intertwined with minerality belies that fact that this is a second wine. The tannins are remarkably fine, though not as suave as in le grand vin—a lambswool versus cashmere kind of comparison. Enlivening acidity keeps the fleshy 2016 Les Fiefs alive and bright and balances its ripeness. You feel the glossiness imparted by oak aging (14 months, only 20 percent new) without tasting the wood. Bordes explains that “oak is the fourth grape variety,” and you need to be careful not to overwhelm the wine. The blend is Cabernet Sauvignon 55%, Merlot 41%, Petit Verdot 4%. Drinking window: 2023-2033.

Château Lagrange 2016 Saint Julien Cru Classé 97

The extraordinary 2016, one of Lagrange’s best, combines the elegance of the 2009 with the power of the 2010. It delivers the impeccable balance of dark fruit and minerals, all wrapped in silky tannins. Weighing in at 13.7 percent alcohol, the 2016 is elegant, not overdone, with uplifting freshness that amplifies it charms. A subtle hint of bitterness in its astonishingly long finish adds to its appeal. Despite the sizeable (70%) amount of Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend, its velvety texture makes it approachable now. Bordes reports that the key was “picking at the right time.” The risk, he continues, was succumbing to the temptation to wait to achieve a little more ripeness since the weather during harvest was fine. The danger, of course, was to wind up with overripe grapes and over extracted wines. Bordes avoided both those pitfalls in 2016. A blend of Cabernet Sauvignon 70%, Merlot 24%, Petit Verdot 6%Drinking window: 2026-2056. .

Château Lagrange 2015 Saint Julien Cru Classé 92

Rain in September weakened what could have been a great vintage, according to Bordes. He needed to include a relatively high percentage (8%) of Petit Verdot in the blend to compensate. That said, succulent black fruit compliments the subtle earthy tones. A lovely, slightly herbaceous character, is emerging, indicating the 2105 is just starting to enter its mature phase. The tannins are fine, not as suave as the those of the more youthful 2019, but not intrusive or distracting. A blend of Cabernet Sauvignon 75%, Merlot 17%, Petit Verdot 8%Drinking window: 2024-2044.

Château Lagrange 2010 Saint Julien Cru Classé 95

Powerful, yet tightly closed, the massive 2010 Lagrange tastes far younger than the 2015. You’d never guess the meaty mineral-packed 2010 is 13 years old. While extracted and concentrated, the muscular 2010 is balanced, though with more apparent tannins at this stage. This fresh and full-bodied youthful wine opens a touch as it sits in the glass. That said, the 2010 really needs years more to reveal itself. Bordes describes it as a classic, ripe “old-style” vintage with “al dente” tannins in the finish that will age beautifully. Cabernet Sauvignon comprised 75 percent of the blend. He didn’t include any Petit Verdot in the blend in 2010 because, as he noted, “it didn’t need it.” A blend of Cabernet Sauvignon 75%, Merlot 25% (95, Drinking window: 2026-2063.

Château Lagrange 2009 Les Fiefs de Lagrange Saint Julien Cru Bordeaux 92

Despite being ready to drink earlier than le grand vin, Les Fiefs also develops nicely over a decade or so. The mid-weight 2009 Les Fiefs now displays cedar and engaging savory leafy notes with fewer mineral notes. As with the younger version, the tannins of the 2009 Les Fiefs are a touch coarser than those of le grand vin. But frankly, if drunk by itself instead of side-by-side with its big brother, one could be excused for not identifying it as a second wine. A blend of Cabernet Sauvignon 57%, Merlot 35%, Petit Verdot 8%. Drinking window: 2023-2030.

Château Lagrange 2009 Saint Julien Cru Classé 96

The gorgeous and impeccably balanced 2009, the first vintage for which Bordes had full responsibility, delivers a distinct dark minerality enrobed by a suave texture. Long and silky, it’s far fresher and livelier than the more powerful 2010. Bordes notes the blend was nearly identical for the two vintages, so the difference was likely just the vintage conditions. Still youthful, the voluptuous 2009 expresses the first hint of maturity, making it hard to resist for drinking now. Its profile Just less than half of the total production made it into le grand vin in 2009, which helps explain its grandeur. Cabernet Sauvignon 73%, Merlot 27%Drinking window: 2023-2053.

Château Lagrange 2005 Saint Julien Cru Classé 93

Leafy nuances indicate that the 2005 is ready, while the nicely integrated tannic backbone suggests there’s no rush. A marvelous interplay between savory notes and black currant ones adds enormous appeal. The even split of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot (roughly 45 percent each) is characteristic of pre-Bordes vintages. The tannins are slightly less refined that those of more current vintages but are not intrusive. Bordes believes the inclusion of nine percent Petit Verdot helps the texture. The blend is Cabernet Sauvignon 46%, Merlot 45%, Petit Verdot 9%. Drinking window: 2023-2043.

Château Lagrange 2003 Saint Julien Cru Classé 90

The 2003, a product of the first swelting (climate-change) vintage, has turned out far better than anyone would have expected. Sticky tannins support the ripe black currant and slightly prune-y fruit in this blend, while licorice-like notes add an appealing contrast. The acidity is surprisingly good given the scorching heat of the vintage. Bordes believes the way the 2003 has evolved shows that Lagrange’s terroir is nicely equipped to handle global warming. Cabernet Sauvignon 57%, Merlot 33%, Petit Verdot 10%. Drinking window: 2023-2030).

Château Lagrange 2000 Saint Julien Cru Classé 95

Prior to the 2019 Lagrange, the 2000 contained the lowest percentage of wine for le grand vin, a measly 34 percent of the production. Ducasse’s feeling was that it had to be superb because of the of notoriety of a vintage that ended with three zeros. Perfumed and plush, the voluptuous 2000 exudes a blissful combination of minerals and dark cassis-like fruitiness accented by a touch of savory smokiness. Its freshness and length are beguiling. With 76 percent Cabernet Sauvignon, it predicts—and predates—the modern blend. Cabernet Sauvignon 76%, Merlot 24%. Drinking window: 2023-2043).

Château Lagrange 1996 Saint Julien Cru Classé 96

The gorgeous, fully mature 1996 demonstrates why people should cellar top Bordeaux. The interplay of tobacco and cedar aromatics with fresh and dried fruits—and a touch of meatiness as well—dazzles the palate. The seamlessly integrated tannins lend support to this graceful wine. At 25-plus years of age, the 1996 Lagrange remains fresh and lively, without a hint of fatigue. Bordes notes they had to chapitalize the ’96 because it was such a cool year was a cool year—does not seemed to have harmed it. Cabernet Sauvignon 57%, Merlot 36%, Petit Verdot 7%. Drinking window: 2023-2033.

Château Lagrange 1990 Saint Julien Cru Classé 88

The clearly mature and burly 1990 was a disappointment especially given the stature of the vintage. Uncharacteristically, it lacked generosity despite the introduction of Petit Verdot to the blend. Drying tannins detracted from the sweet fruit. Bordes felt that a touch of Brettanomyces stripped the wine. Cabernet Sauvignon 44%, Merlot 44%, Petit Verdot 12%. Drinking window: now.

Château Lagrange 1983 Saint Julien Cru Classé 91

The previous owners made the now fully mature and gamey 1983 Château Lagrange, but Ducasse not doubt improved it by creating Les Fiefs that year. Upon pulling the cork, the wine was quite funky, but cleaned with aeration to show graceful maturity, meaty concentration, and suave tannins, all accentuated by freshness. The blend is approximately Cabernet Sauvignon 55%, Merlot 45%Drinking window: now.

Château Lagrange 1982 Saint Julien Cru Classé 94

Even with the neglected vineyards, indifferent wine making, and no second wine, the meaty and mature 1982, from a pre-Suntory vintage, shines. It shows the fundamental importance and depth of Lagrange’s terroir as well as the grandeur of the vintage. Despite black tea aromas that Bordes attributes to perfectly ripe Cabernet, the succulent 1982 displays a captivating Pomerol-like exotic profile. The suave tannins allow the long and fresh finish to shine. Drinking window: now.