It’s better to be lucky than smart.

Of course it’s better to be both, like Miljenko “Mike” Grgich. Time after time, he’s been in the right place at the right time, although at the time, neither the place nor the situation seemed appealing. But in each instance he’s been smart enough to take advantage of what came his way, “turning lemons into lemonade.”

Naturally, Grgich is known for his Grgich Hills Estate winery, which makes some of California’s best wines. To me, Grgich Hills Estate’s  ability to produce equally stunning red and white wines is what places him among the world’s best producers.

ability to produce equally stunning red and white wines is what places him among the world’s best producers.

But far more significantly, it was Grgich who was responsible for drawing the world’s attention to Napa Valley, and by extension, to California wines. He forced the wine world to take California wines seriously when the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay, which he made, beat out some of Burgundy’s top whites at the famous “Judgment of Paris” tasting in 1976.

Although his nickname is Mike, it could just as easily have been “salmon,” as he tells it. He describes a formative experience from his youth when, in Canada, he watched salmon on a run upstream to their spawning site. He marveled at how a fish would jump relentlessly at the waterfalls until it finally made it over. His creed amplified his father’s advice: Work hard–be persistent.

His story epitomizes the American dream.

From Zagreb to Germany to Canada

Born in Croatia in 1923, Grgich, the youngest of eleven, he had the good fortune to spend his childhood among the vines, as his father was a noted winemaker. Grgich remembers his father’s advice and dispenses it today, “Work hard and learn one new thing a day. That way, after a year you will be a better person.” After his parents died while he was still young, an older sister raised him.

Later, having already earned a degree in business, he enrolled in the University of Zagreb to study viticulture and enology in 1949–only to have his studies interrupted when the communists came to power in Yugoslavia. Living in Zagreb then was not easy. He recalls walking with a mattress made from cornhusks from his home to where the communists had imprisoned his sister so that she wouldn’t have sleep on the cement floor of her cell.

Grgich left the University of Zagreb before graduating because he was fortunate to receive a UN-sponsored fellowship and a visa, in 1954, to emigrate to Germany, where a generous family took him in. But before he left he studied plant genetics, which turned out to crucial in solving a problem that had long plagued German agriculture. After a rain, wheat would droop so low that the grain would touch the ground and rot. Grgich helped insert genes from rye, which remained upright after a rain, into wheat, a modification that kept the shoots upright and out of the water.

He longed to go to America, but, despite his talents, was denied a visa. Undeterred, he convinced the Canadians to grant him a visa, emphasizing his agricultural training. Money for passage to Canada was supposed to arrive from a brother-in-law already living in America. When it didn’t, Grgich was lucky that the family with whom he was staying in Germany advanced him the $50 he needed. He sailed to Canada where he was supposed to cut trees in the Yukon. Luck struck again as he missed the train to the Yukon and wound up instead in Vancouver. Having heard about the “paradise” of the Napa Valley from a former university professor, he set out to go there. He placed an ad in a California newspaper where Lee Stewart, owner and winemaker of Souverain Cellars, read it and offered him a job and more importantly, sponsored his immigration application.

Napa Valley

Grgich finally fulfilled his dream of coming to America when he arrived to work for Souverain in August of 1958.

His big break came when André Tchelistcheff, California’s most talented winemaker at the time, hired him to work as a chemist in the lab at Beaulieu Vineyards. Though Grgich knew European analytic methods, the American system of ounces was as foreign to him as the English language. But he was persistent and impressed Tchelistcheff during his test period. Tchelistcheff raised his salary from $2 to $3 an hour, an enormous increase since he had been making $100 a month at Souverain. But the raise didn’t come without responsibility. Grgich wanted to get married in September of 1962, but Tchelistcheff insisted, “You cannot until crush is finished.” Harvest was late that year, ending on the 15th of November. Grgich married 2 days later.

After Grgich left BV, he was winemaker for Robert Mondavi for four years and made Mondavi’s famous 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon, which was selected as California’s best Cabernet at a prestigious tasting organizer by Robert Balzer of the Los Angeles Times. Then, in 1972, he joined forces with Ernie Hahn and Jim Barrett as winemaker and limited partner at Chateau Montelena, where he made that world-awakening 1973 Chardonnay. Grgich may have been lucky to have the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay included in the Paris tasting. But it certainly was not luck that placed it first. It was Grgich’s skill as a winemaker.

In 1977, to establish his own winery, Grgich went into partnership with Austin Hills of Hills Brothers Coffee and Hills’ sister, Mary Lee Strebl. Paul Landeros, an independent viticulturist who worked for both Hills and Chateau Montelena put Grgich and Hills together. He knew Hills, who already owned vineyards, was looking for a winemaker. They broke ground on July 4, 1977. And the rest, as they say, is history.

It’s Not Just About Wine in Napa

In addition to the awards and accolades Mike Grgich and his Grgich Hills Estate wines have received, he is justifiably proud of his other accomplishments. His viticultural training in Zagreb enabled him to notice the similarity between Zinfandel and Croatia’s Plavic Mali grape. He helped convince Carole Meredith of the University of California at Davis to research Zinfandel’s origins and was thrilled when his visual acumen was confirmed by DNA testing, which showed that Plavic Mali and Zinfandel arose from a common ancestor.

With the demise of communism and the independence of Croatia, Grgich thinks a new era for Croatian wines has arrived. Wanting to contribute to that era by helping the local winemakers, Grgich now makes wine, from Pošip and Plavic Mali, in Croatia on the Dalmatian coast. In addition to his enological expertise, Grgich has contributed heavily to landmine clearing projects in his homeland. He is most proud that he has been recognized with two plaques in Croatia–one for wine and one for mine clearing.

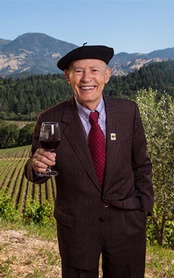

The Beret

Grgich, who just celebrated his 90th birthday, is still vigorous. Though slightly stooped and walking with a cane, he meets the Napa Valley wine train that stops in front of his winery. Wearing his signature beret, he continues to usher people into his tasting room, encouraging them to taste, and also to buy–though after tasting, they need little encouragement.

Some assumed his trademark beret was to remind people that his wine beat the French whites at the Paris tasting. But his beret-wearing preceded that event by decades and reflects his parsimony. He needed to take multiple trams to school in Zagreb, where, according to Grgich, it rains as much as it does in Vancouver. On one trip he left his umbrella behind. Too poor to buy another one, he bought a beret instead which, he noted, he would never lose because it would either be on his head or folded in his pocket. His original beret is on display, along with the cardboard suitcase that accompanied him from Croatia, in the Smithsonian Museum of American History, along with another icon of Americana, Julia Child’s kitchen.

When he arrived in United States, he relates how he was always searching for a link to Croatia. He scoured telephone books and whenever he found a Grgich, he would call and inquire–are we cousins? Are we related? Always the answer was no. Amazingly, now that he is successful and famous, he notes that people are always calling him insisting they are cousins.

A Modest Man

Despite his extraordinary success, Grgich remains a modest man, quick to thank everyone who has ever helped him. He remembers how, in the mid 1990s, Robert Mondavi invited him back to discuss the 1969 Cabernet when Mondavi was hosting a vertical tasting. Grgich was embarrassed that Bob, who knew everything about that wine–and all the other vintages–had invited him back even though he had worked with Mondavi for only 4 years. “That was the kind of person Robert Mondavi was–he was a generous man.”

Grgich always sees the positive side of things: “I failed at many things, but succeeded at more. . . I don’t talk about my mistakes.” He eventually had a falling out–to put it mildly–with Jim Barrett, the principal owner of Chateau Montelena, who barely acknowledged Grgich’s role in the Paris tasting. But when asked about it, Grgich takes the high road, “I’m thankful he gave me a job and the opportunity to make great wine.”

Grgich speaks with real sadness at the difficulty of leaving Croatia. “It’s not easy to leave your home, your family, your language, your culture. . . Freedom was my draw.” He persisted in his dream for freedom, first going Germany, then to Canada and finally to the US. It’s appropriate, though purely by luck, that the event that catapulted Mike Grgich and California onto the world’s wine stage was organized by Steven Spurrier to celebrate America’s Bicentennial. However, the date he chose to break ground for his winery, July 4, was not selected by chance and speaks volumes about Mike Grgich.

Winemaking Philosophy

Grgich’s winemaking philosophy is really quite simple: “Let the grapes speak. You need to preserve what’s in the grape. What’s made by God is always better than what’s made by man.” He continues, “You can measure acidity and sugar. You can’t measure aromas or complexity. You must taste.” He recounts once coming home to lunch just when harvest was about to start and not eating what his wife had just prepared. She was hurt. He explained, “I’ve just been tasting pounds of grapes.”

He points out that often in the current environment, “The winemaker wants to speak,” and observes, drawing on his Croatian background, that in English, “I” is written with a capital letter and “you” is lower case. In the Croatian language, it’s the opposite. “In California, the “I,” the winemaker, dominates and wants to prove something. Sometimes the something is good, sometimes not.” Winemakers today need to rely on their ‘feelings’ and not just the computer,” Grgich insists. “Feelings are superior to computer when making wine.” He concludes, “Wines that are balanced–the acid, the alcohol, the aroma–will last long, like a family.”

With his signature broad smile, a sign of a man who is clearly content with himself, Grgich continues, “You need one foot in the vineyard and one foot in the winery and one foot in the market place. That’s why I have a cane, so if the merchants don’t sell my wine, I can beat them.”

Persistence

In 1995, at age 77 and 41 years after leaving Croatia, Grgich, like a salmon, returned to the University of Zagreb, to receive, at long last, his degree in enology and viticulture.

Grgich is leaving the winery in good hands. About 25 years ago, he brought on his daughter Violet and his nephew Ivo Jeramaz so, as he puts it, “I could spend time in Palm Springs.” Always full of praise, “They run the winery better than I did.”

Grgich remains in the picture. He insists on organic viticulture because, as he puts it, “It’s better for the wine, the environment and leaves something for the next generation.” However, he is skeptical about biodynamics, and consequently was glad that Jeramaz converted Grgich Hills Estate to biodynamic production while he was still around, “So I can be sure there was no decrease in quality.”

June 25, 2013