The whole world, and not merely the wine world, lost a giant this month when Peter M.F. Sichel died peacefully at his home in Manhattan at the age of 102 and-a-half.

The whole world, and not merely the wine world, lost a giant this month when Peter M.F. Sichel died peacefully at his home in Manhattan at the age of 102 and-a-half.

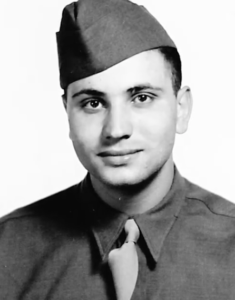

Peter’s life story is well-known. Born into a family of wine merchants—his grandfather founded H. Sichel Söhne in 1857—he and his family became refugees, escaping the tyranny of Nazi Germany. Soon after reaching America, he joined the army and was recruited into the OSS (Office of Special Services, the celebrated World War II forerunner of the CIA) because of his fluency in German, English and French.

After the war, he was active in the CIA’s Berlin office, where he ran a large and critically important counter-intelligence group. Later he headed the CIA office in Hong Kong. For his exemplary service to the Nation, he was awarded the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, one of the agency’s highest awards. Sichel figured prominently in Scott Anderson’s highly acclaimed book about the U.S. intelligence service, The Quiet Americans (Doubleday, 2020).

His career in the wine trade was legendary. After he left the CIA—he disagreed with some of their tactics—he returned to the family business, introducing Americans to Blue Nun, which at one point was the most widely imported wine on the U.S. market. For years, Sichel was also the managing director of the prominent Bordeaux négociant, Maison Sichel. The family still has a controlling interest in famed Château Palmer, classified as a third growth in the Médoc Classification of 1855. Peter was also the principal owner of another Bordeaux property, Château Forcas Hosten in Listrac until Laurent and Renaud Mommeja, owners of Hermès, purchased it in 2006. For his many years of service to the wine trade, The Wine Spectator awarded Peter its Distinguished Service Award in 1989.

But despite all those accomplishments, Peter’s willingness to help others defined him. It set him apart. It was his central trait, his core principle. His default. Something that was ingrained in him, perhaps from the help he and his family received escaping Nazi Germany. Or perhaps it was simply a part of the Sichel family DNA. As Peter recounted in his autobiography, with the onset of the economic crises of 1929, his mother always made him two sandwiches for the 10 o’clock snack at grade school, teaching him to share one with those whose who needed it.

Throughout the long and cold winters of the Depression years, she welcomed and fed the poor by setting up a table and chairs on the back porch. Or maybe he got it from his father, whom he described as, “Helpful whenever possible.” Maybe he learned it from his mothers’ sisters, all of whom he described as, “Motivated by a rare sense of decency.” And his willingness to always go the extra mile may have come from, as he puts it, “A strong Jewish community structure—born through pogroms and discrimination—through which those of the Jewish faith could help each other.”

That rare and all too-elusive trait of always wanting to lend a hand is what made Peter so special. As word of his death spreads, the anecdotes that people have shared do not involve his great success as a wine merchant or as a spy. They centre around his kindness and generosity with his time. As Maryann Dolzadalli, Peter’s personal assistant, notes, “After 25 years with Peter I have seen people from all corners of the world contact him for help of some kind or other.” She adds, “He never turned them away.”

Jean-Louis Carbonnier, the former U.S. representative of The Champagne Bureau, later of Château Palmer, and now the U.S. representative for Château Talbot, describes Peter as “The number one networker,” and explains that Peter so often facilitated deals and relationships, not for his own profit, but for altruism. He was not egotistic and never asked for anything in return. Even after the popularity of Blue Nun faded, adds Jean-Louis, “I’ve never heard him sound bitter about anything.”

Charles Curtis, MW, Burgundy correspondent for Decanter and founder of the fine wine advisory company, WineAlpha, remembers Peter as “an invaluable mentor to me in my career,” and recounts how Peter helped arrange a trip to Bordeaux for him, the experience of which he says played a large part in his obtaining his MW.

Michael Quinttus, the founder of Vintus, a leading U.S. importer, emphasizes, “Peter literally opened the door for me to enter the wine business.” He recalls, how he met Peter in the 1980s, when, as a lawyer, he represented a German company promoting German wine in the U.S. Michael soon shared his passion about wine with Peter and explored the possibility of leaving law to enter the wine trade.

Michael recalls that Peter was a great sounding board, “taking me under his wing.” Michael recounts how Peter told him, “I will be your Rabbi.” Peter sent a letter to Charles Mueller, then the head of Kobrand, a major U.S. wine importer, and a competitor of Schieffelin and Somerset who were importing Peter’s Blue Nun, suggesting they talk with Michael. They did and they eventually hired him. Michael insists, “Peter made it happen.”

At the heart of this story is Peter’s altruism. He was helping Michael because that was Peter’s character.

Years later, Peter suggested to Michael that he should speak with Alex Michas, the son of a friend of Peter’s who was interested in entering the wine trade. As Michael tells it, Peter wanted him to point out the stumbling blocks and dissuade him. Michael saw what a gem Alex was, hired him and now, Alex is the President of Vintus. Here’s another of many examples of how Peter put people together—a deal maker without taking a cut.

To me, Peter’s ever-present smile and how-can-I-help character are his defining features. The world needs more people like him, especially now.

He will be missed.

Originally published in Jane Anson Inside Bordeaux, March 4, 2025, with huge thanks to John Anderson (no relation to Scott), also a good friend of Peter’s, for his editorial prowess.