“This could be the crash of the century instead of the vintage of the century,” quipped Coco Conroy of Château Brane-Cantenac, a second-growth property in Margaux, as she jokingly referred to Bordeaux’s 2008 vintage.

Like other blue chips, Bordeaux, the bluest of blue chips in the world’s wine market, is not immune to this economic downturn. The Bordeaux market is currently in chaos. Buyers are reluctant to step up to the plate. Prices are falling sharply. It is possible that Bordeaux’s long-established, and intricate, system of selling wines faces fundamental change.

Bordeaux has seen crisis before in the early 1970s and early 1990s. The major difference now is that Bordeaux represents a much smaller portion of the overall wine market. And back then, importers had to buy Bordeaux for their portfolios; without it, they were not credible.

Now Bordeaux represents a much smaller portion of the overall wine market. Despite its shrinking share, Bordeaux prices have risen – at least until now – like a rocket, making it much more capital-intensive than any other types of wine.

Hence it is far less important and far more risky for an importer to handle Bordeaux than it was even 15 years ago. And this year, with fewer buyers for expensive wines, many importers are shying away.

Historically, Bordeaux sales are predictable. The wines are sold en primeur, a system unique to Bordeaux, in which the wines are sold in advance – as “futures” – two years before they are bottled and shipped to retailers. (Unlike buying pork belly futures, the consumer typically wants to take delivery of the wine.) Buyers and critics troop to the region the first week of April every year to attend organized tastings of the new vintage and to assess the wines.

Once the reviews of critic Robert Parker come out, usually in May or June, individual chateaux set their prices. Prices generally move in the same direction – usually up compared with previous years – but by varying degrees depending on the reviews.

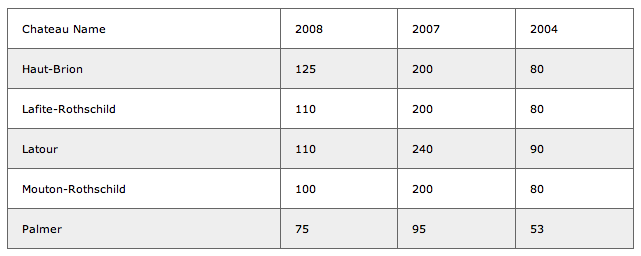

But this year, to jump-start the market, some set prices even before Parker weighed in. Most have dropped substantially. Chateau Angelus, a top St. Emilion and the first to announce prices, cut its price almost in half, to 2004 levels. Even the sought-after first growths – Chateau Haut-Brion, Lafite-Rothschild, Latour, Margaux and Mouton-Rothschild – who always easily sell their wine and who usually announce their prices last, have already posted dramatic decreases compared to prior years. Latour’s initial price of 110 euros was less than half the 2007 price.

Impact on 2007 prices

The price drops sent a tsunami through the retail market. Many 2008s are selling for less than the 2007s, an inferior vintage by all accounts. Retailers around the country are slashing prices – and taking losses – on unsold 2007s and even 2006s. MacArthur Beverages in Washington, D.C., just slashed the prices on its stocks of 2006s by 50 percent. Mark Wessels, MacArthur’s Bordeaux buyer, expects something similar for the 2007s. “Who’s going to buy the 2007 l’Angelus for $199 when the 2008, a better wine, is selling for $99?” he asks.

Clyde Beffa Jr., who buys Bordeaux for K & L Wine Merchants in San Francisco, anticipates taking a loss on his 2007s, but customers have responded to the lower-priced 2008s. He points to Chateau Leoville-Barton, a well-regarded St. Julien, for $44: “It’s hard to find good California Cabernet at that price.”

So there’s strength for some wines. Parker, whose reviews came out in late April, praised the vintage in general and Lafite in particular, causing its price to double. But up until the publication of Parker’s assessments, buyers were showing far less interest in the 2008s.

This year, Bordeaux’s en-primeur week was missing some habitually large purchasers – including Wessels and Beffa. Attendance was down overall by about 10 percent.

The weak demand and falling prices prompted some producers to consider abandoning the whole system, at least temporarily. Typically, the en primeur system shifted power toward producers; they have been reluctant to give it up because it provides owners with early sales and an ability to test the market by releasing only part of their stock. Lafite’s preliminary Parker score of 98-100, for instance, allowed them to dramatically raise prices for their remaining stocks of 2008s. But that has been the exception.

“The 2008 en primeur campaign isn’t going to work,” according to John Kolasa, director of Chateau Rauzan-Ségla in Margaux and Chateau Canon, a leading property in St. Emilion. He thinks the prudent thing to do is to “recognize the horrible economic situation and hold wines for a couple of years.”

Some holding back

Patrick Maroteaux, president of Château Branaire-Ducru, a top property in St. Julien, is considering a similar tack. “People are clamoring for me to reduce my price by 50 percent,” he says, “which would mean that I would be charging less for my 2008, a much better wine, than for the 2007. And there’s no guarantee that it will sell even at that price.”

A few properties, including the prestigious Chateau Pichon-Longueville (Baron), adopted this strategy in the early 1990s during a similar economic turndown. But many estates simply need the cash. Others aren’t willing to abandon tradition. Jean-René Matignon, technical director at Pichon-Longueville (Baron), expects management to sell at least a portion of the 2008 vintage en primeur.

Large-scale buyers are just as hesitant to place orders in an uncertain economy-especially at prices they may not be able to pass onto their customers-for fear of being stuck with wines they cannot sell. Volatile currency exchange rates – the dollar has fluctuated against the euro by 20 percent in the last six months – only make things worse. Yet those who fail to buy the 2008s could face retaliation from producers, who could punish them by refusing to sell them their allocation in the future.

Given its hidebound ways, it is improbable that the en primeur system even survived this long, especially given Bordeaux’s shrinking dominance of the world of wine. It served an important function when most chateaux were short of cash and wines needed prolonged aging. But now there is less barrel aging and the wines are consumed sooner. With so many other regions producing similar wines, it’s surprising that the Bordelais – but no one else – still persuade buyers to pony up two years in advance.

More reluctance

So this year’s turbulence may change the game. Fred Ek, a principal of Ex Cellars Wine Agencies, an importer based in Cambridge, Mass., and Solvang (Santa Barbara County), says importers in general are leery of putting money up front now.

“Just look at the last two years,” Ek says. “The economy is unstable. The currency risks are substantial. It doesn’t make sense to take a greater risk to capture a smaller portion of the overall wine market.”

Although it’s hard to envision Bordeaux’s long-established system disappearing entirely, the economy is accelerating the trend of some of its players abandoning it.

Bordeaux price plunge

Some initial release prices for Bordeaux chateaux in 2008 show marked drops from previous years. Prices are in euros per bottle. Currency rates have created further instability: The euro was about 1.29 for the 2004s; 1.55 for the 2007s and about 1.32 for the 2008s.

Source: Decanter, Chateau Palmer

This article appeared on page J – 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle on Friday May 10, 2009